To date, few universities offer epidemiology as a course of study at the undergraduate

level. Many epidemiologists are physicians, or hold other postgraduate degrees

including a Master of Public Health (MPH), and Master of Science or Epidemiology (MSc.). Doctorates epidemiologits may hold include the Doctor of Public Health (DrPH), Doctor

of Pharmacy (PharmD), Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), Doctor of Science (ScD), or for

clinically trained physicians, Doctor of Medicine (MD) and Doctor of Veterinary Medicine

(DVM).

As public health/health protection practitioners, epidemiologists work in a number of

different settings. Some epidemiologists work 'in the field'; i.e., in the community,

commonly in a public health/health protection service and are often at the forefront of

investigating and combating disease outbreaks.

Other epidemiologists work for non-profit organizations, universities, hospitals and

larger government entities such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

or the World Health Organization (WHO).

We have included a glossary of terms imbedded at the end of this section since

epidemiology uses very different terms from other research fields.

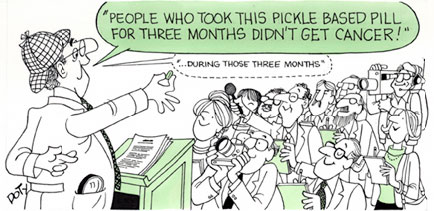

Determining Cause

Although epidemiology is sometimes viewed as a collection of statistical tools used to

elucidate the associations of exposures to health outcomes, a major function of this

science is that of discovering causal relationships.

Cancer is not a single disease, but the generic name for more than 200 diseases, all

having in common the uncontrolled reproduction of abnormal cells. Although scientists

have only recently begun to understand the causes and growth patterns of cancer, there

exists a large and growing body of evidence showing that daily choices about diet,

physical activity, carcinogen exposures and weight management play a role in cancer

risk.

Epidemiologists use collected data and employ a broad range of biomedical and

psychosocial theories in an iterative (each fact builds on the next) way to generate or

expand theories, to test hypotheses, and to generate educated, informed decisions

about which relationships are causal for a disease, and about exactly how they are

causal.

Epidemiologists Rothman and Greenland emphasize that the "one cause - one effect"

understanding is a simplistic misbelief. Most outcomes, whether they be disease or

death, are caused by a chain or web of events consisting of many component causes.

For example, do cigarettes 'cause' lung cancer? The weight of the observational

evidence showed that tobacco use was related to a large number of cancers.

Epidemiologists published these findings. As people decided to stop smoking, the rates

for these cancers started plummeting.

Does this mean that epidemiologists understand the mechanism by which tobacco

smoke produces cancer in humans? No they don't and actually, neither do basic

researchers, although they have a myriad of hypotheses.

| |

|

| |

| Image courtesy of American Institute of Cancer Research |